Cooperative Aerial Transportation

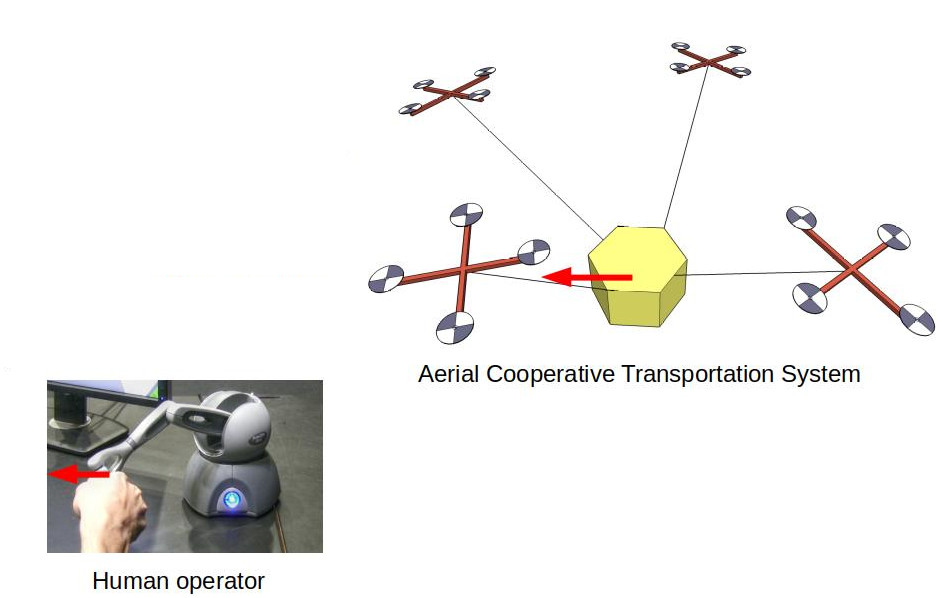

a cable-suspended payload transported by a team of micro UAVs

Aerial robots have been growing considerably in popularity and interest, both in terms of pure research, where it is a stable topic of discussion at all the major robotics conferences and journals, and in terms of real-world applications, where these platforms are now widely used in agriculture, monitoring of infrastructures, entertainment industry, etcetera. This growth is reflected in the appearance of ever more complex tasks to be performed with aerial robots. One such task is the cooperative transportation and manipulation of objects using micro UAVs. My contribution to this field has been to introduce the concept that a cooperative transportation system composed by several UAVs connected to the payload by cables can be regarded as a Cable-Driven Parallel Robot (CDPR) and thus it can be studied with the well established methods that have been in use in that field for a long time. Actually, this aerial transportation system is a generalization of a CDPR because the anchor points in the aerial system (the UAVS) can move whereas in traditional CDPR the anchors (winches) are fixed.

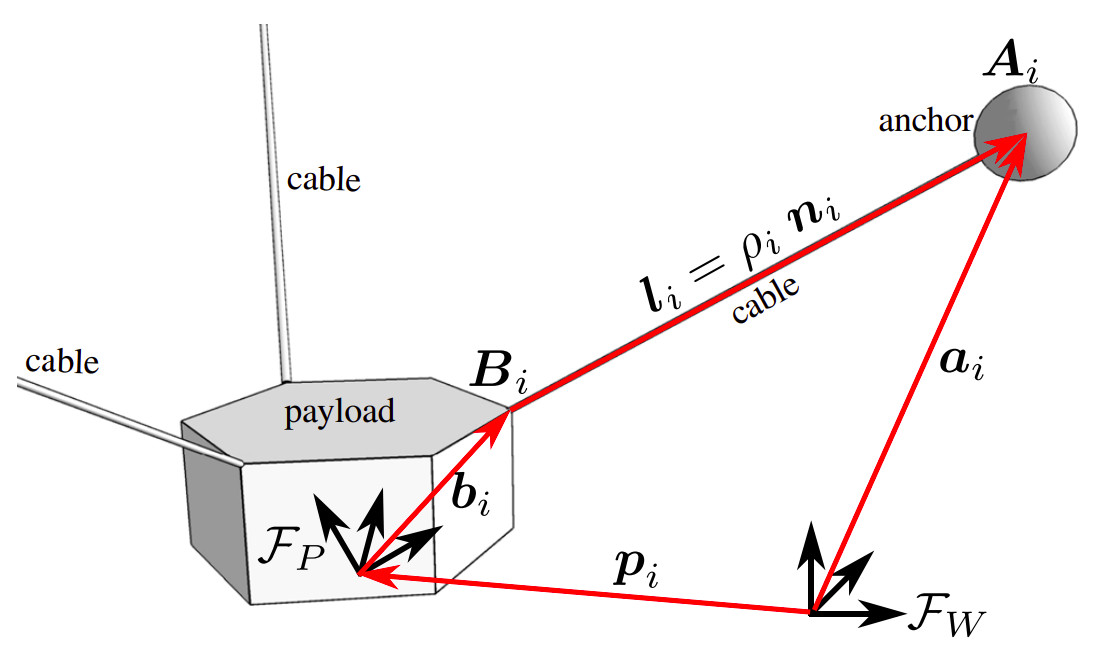

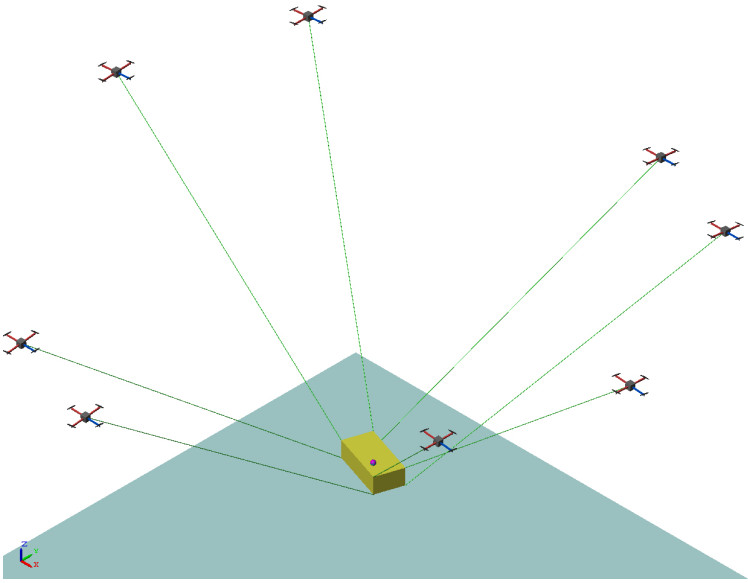

Considering this intuition, and with the visual help of Fig. 1, we can write the loop closure constraint for a single cable as

\[{}^W \boldsymbol{l}_i = \rho_i \; {}^W\boldsymbol{n}_i = {}^W \boldsymbol{a}_i - {}^W\boldsymbol{p} - {}^W \boldsymbol{b}_i\]This is the classical loop closure equation for a CDPR. However, for CDPRs in general the anchor point \({}^W \boldsymbol{a}_i\) and the cable length \(\rho_i\) can change. For the aerial transportation system it is the opposite, thus with \(m\) cables there are \(m \times 6\) degrees of freedom. In the paper Cooperative transportation of a payload using quadrotors: A reconfigurable cable-driven parallel robot we show that we can rewrite the loop-closure constraints for all cable in a compact form

\(N \boldsymbol{\rho} = \boldsymbol{\chi} - \boldsymbol{\xi}\) where \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\) is the vector of cable lengths, \(N\) is a block-diagonal matrix with the cable directions, \(\boldsymbol{\chi}\) is the vector of the stacked anchor positions and \(\boldsymbol{\xi}\) is the vector of stacked points where the cables are connected to the payload. We further demonstrate that the trajectory of the anchors, denoted by \(\boldsymbol{\chi}\) can be decomposed into two vector spaces:

- \(\mathcal{R}(N)\), that is the \(m\) dimensional range space of \(N\). These are the motions of the anchors along the direction of their corresponding cables, and are the motions that instantaneously affect the payload.

- \(\mathcal{K}(N)\), that is the \(2m\) dimensional null space of \(N\). These are the motions of the anchors that are orthogonal to the direction of their corresponding cables, and they do not affect instantaneously the payload. Namely, these are the internal motions of the system

This formalism exposes the possibility to exploit the internal motion of the system to adaptively achieve various objectives during operations depending on the current state of the system and of the environment, e.g. maximixing the stability of the payoad when there is an external disturbance or reducing the energy consumption of the UAVs to extend the flight duration.

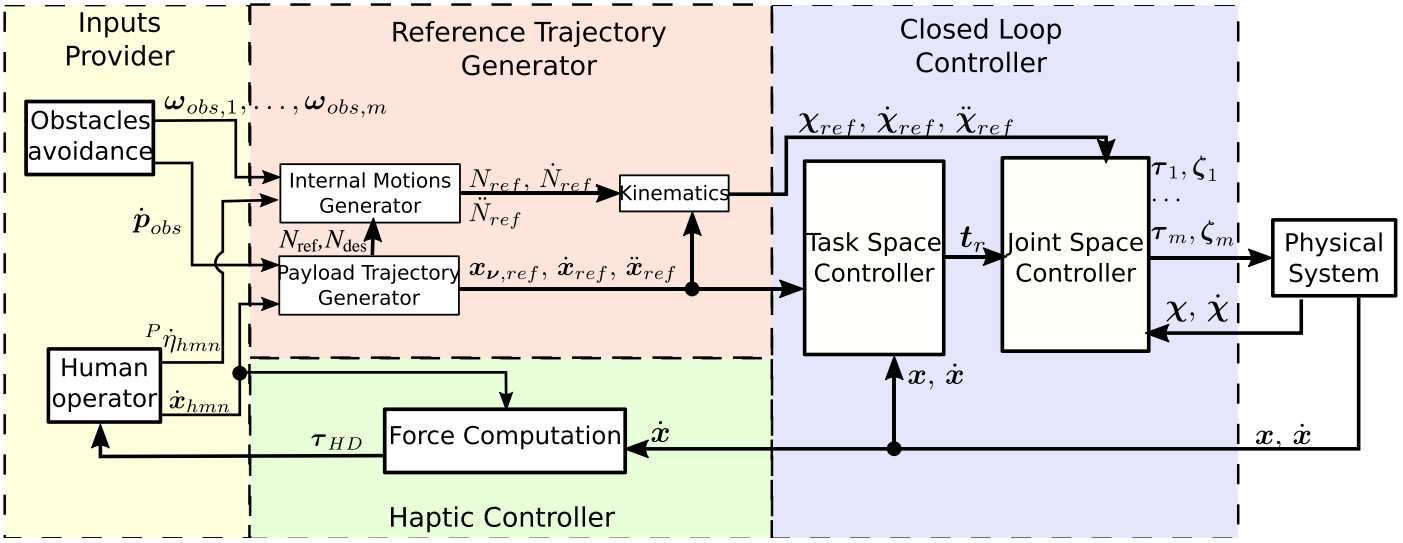

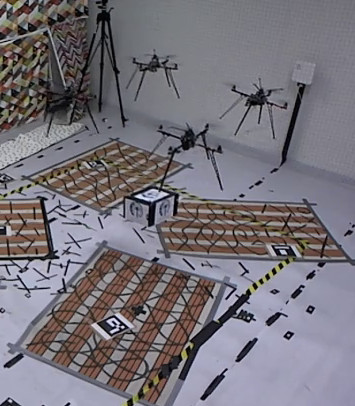

Building on this formalism we created a dual space control system based on solutions available in CDPR, and we demonstrated it both in simulation and with experiments as shown in Fig. 2. It was also further extended with the developmetn of a shared control framework tailored to allow a single human operator to manipulate the transported payload disregarding the individual behavior of the UAVs, while at the same time exploiting the extra degrees of freedom from the internal motions to perform obstacle avoidance and to reshape the formation.